Restricted stock is stock that is subject to forfeiture to the company for no additional consideration or repurchase by the company at the original price paid, if any, until it vests. The number of shares of stock that are subject to forfeiture or repurchase at the purchase price decreases over time in a way that is similar to the way that options vest over time. Restricted stock is issued pursuant to a Restricted Stock Agreement with the company. Restricted stock is a form of stock award preferable to some recipients for tax reasons usually when a company has only been formed a short time. It is generally not available for most employees. Founders frequently take restricted stock. See Should founders take restricted stock?

What are anti-dilution protective covenants?

Anti-dilution protective covenants are commonly seen in preferred stock documentation. The purpose of anti-dilution covenants is to protect early investors in the event of a “down round”. A down round is when shares are sold for a lower price than that paid by investors in earlier rounds. Anti-dilution covenants are a contract requiring the company to issue more shares to early investors if the company sells shares to later investors at a price below that paid by the earlier investors. How many shares the earlier investors are entitled to depends on the formula in their anti-dilution covenant.

There are three basic types of anti-dilution formulas: full ratchet, broad-based weighted average, and narrow-based weighted average.

- Full ratchet — Puts shareholders in the same position as if they had made their invest at the new lower price. The conversion price is simply changed to the price of the down round. This formula can result in significant number of shares issued to earlier investors, and make it very difficult to rise capital later on. It was more common in the dot-com era, but not seen often now.

- Broad-based weighted average — See the formula below. This is the most common kind of anti-dilution formula, and is usually not objected to by later shareholders.

- Narrow-based weighted average — Usually yields a larger share adjustment than broad-based weighted average. It is seldom seen now.

Broad-based weighted average formula for preferred stock:

The new conversion price, NCP, for shares with the anti-dilution right in case of a down round, is calculated as follows:

NCP = CP x (CS + AC/CP)/(CS + AS), where

CS = Common stock outstanding before the down round.

AC = Aggregate consideration paid in the down round.

CP = Conversion price before the anti-dilution adjustment.

AS = Number of shares (on as-converted basis) issued in the down round.

To get a sense of how large an adjustment would be, the key term to consider is AC/CP. This is the amount of shares that could be purchased with the new consideration if the new shareholders were buying in at the earlier, higher price. Since CP is higher than that being paid in the down round, the term AC/CP, will be smaller than AS, the number of shares actualy being purchased in the down round. Since the fraction (CS + AC/CP)/(CS + AS) is less than one, NCP, the new conversion price for earlier class of stock, will be lower than CP, what it paid. Lower is good for earlier investors, because they will get more shares when it becomes time to convert their stock into common.

It is called weighted average, because the adjustment that early shareholders are entitled to is a function of shares outstanding and shares issued in the down round. Note that the size of the down round — AS — must be fairly large relative to shares outstanding, and there needs to be both a fairly significant difference between the original price and the down round price for the anti-dilution adjustment to yield a lot of extra shares to the earlier investors.

Narrow-based weighted average formula for preferred stock:

(This is one example, there are variations.)

The basic narrow-based anti-dilution formula is as follows (there are many variations):

The new conversion price, NCP, for shares with the anti-dilution right in case of a down round, is calculated as follows:

NCP = X1 + X2/Y1 + Y2, where

X1 = Aggregate consideration paid for shares in the earlier round.

X2 = Aggregate consideration paid for shares in the down round.

Y1 = Number of issued shares of the earlier round outstanding .

Y2 = Number of shares issued in the down round.

In this formula you can play around with the numbers to see that, holding the price of the down round constant, the adjustment will be relatively greater if the down round is larger.

Take a simple case where there are 10 shares outstanding that were purchased for $10 ($1 per share). Consider a down round for $0.5 per share, in Case 1, 10 shares are purchased for aggregate consideration of $5. In Case 2, 20 shares are purchased for aggregate consideration of $10. Case 1 yields an adjustment ratio of .67 , from [(10 +10)/(10+20)]. Case 2 yields an adjustment ratio of .75, from [(10 +5)/(10+10)].

Like I said, this formula is not commonly seen these days.

What is dilution? What is a fully-diluted cap table?

Dilution refers to a decrease in an owner’s percentage interest in the company. If there are 4 million shares outstanding and you hold 1 million shares, that equates to 25% of the outstanding stock. If the company issues another 1 million shares, your percentage ownership drops to 20%, and you have been diluted 5%. Similarly, when stock options or warrants are exercised, existing shareholder are diluted.

A “fully-diluted” capitalization table shows, in addition to all outstanding shares, the number of shares (or units) issuable upon exercise or conversion of the contingent equity. Sometimes the exact number of shares can not be determined. For example, if the the number of shares issuable upon exercise of a warrant may be based on a formula, such as a percentage of gross sales. In such cases, a properly prepared fully-diluted cap table will have footnotes explaining the assumptions underlying the share numbers shown.

Also, with respect to employee stock options, there should always be a footnote on the cap table indicating which calculation is used, because there three possible meanings of “full-dilution” in the case of employee stock options. The three ways to record the the number of stock option shares, starting from largest to smallest, are: (1) the total number of option shares authorized by the stock option plan, (2) the total number of options currently granted, and (3) the total number of options currently vested. Number (1) is used most often and is the most conservative number for management to use. Number (2) makes sense if additional options are not likely to be granted for some time, but the cap table should clearly indicate that only granted shares are shown. Number (3) is rarely used, since options will continue to vest as long as employees stay employed, but in certain cases, for example when there is a long period before the next options vest, it may make sense to include an additional column in the cap table showing vested only options.

Sometimes the term dilution is used in reference to dilution of value, as opposed to dilution of percentage interest. If new shareholders are paying a fair price for their shares, then the value (as opposed to ownership percentage) of existing shareholders’ interests are not being diluted. In general, I would recommend not using the term dilution (or lack thereof) in this way, but you should be aware when others use it in that sense. See “What are anti-dilution protective covenants?“.

What type of entity should I choose, LLC, C corporation, or S corporation?

Deciding whether you should organize as a C corporation, S corporation or limited liability company can soak up a lot of time and resources. Some founders may spend more time on this question than is warranted given the inability to know for sure how quickly your business will grow, how much and which type of outside investment will be required, whether cash will be reinvested or distributed to owners, or whether you will sell the Company or go public – all of which are part of the analysis. Tax rules are the primary source of the complexity, although management and liability issues under state law also make a difference.

Founders tend to fall into two categories when dealing with this issue – those that , with their lawyers and accountants, carefully analyze the various tax rules against their expected growth and exit strategy and try to make the best decision under uncertainty – and those that punt, opting to stick with the format used by most VC-backed technology companies (C corporation) and spend their time and energy on growing their business.

One reason venture capital firms generally will only invest in corporations because they usually have tax exempt investors who do not want to subject to unrelated business income tax (UBIT), which would be an issue with an LLC. Moreover, VC members may not want to file state tax returns, or, in the case of foreign investors, federal tax returns. VCs like some of the other advantages to C-corporations discussed below.

For those that want to dive into the analysis, I discuss the major differences between C corporations, limited liability companies, and S corporations in the second half of this article. Perhaps the best place to start the analysis is to understand why most tech startups are corporations, and to consider what makes your company different, if anything. If not, you may want to follow that model. Since the C corporation is the predominant entity form for tech startups, documentation has become fairly standardized for corporate governance, rights among shareholders, equity compensation, and capital raises.

The top level questions that will affect your choice of entity are these:

- Do you expect to take money from a Venture Capital firm or an institutional investor. In this case, you will need to be a C corporation, although you may be able to start life with an S election while you bootstrap and only convert if it becomes necessary.

- Will you be a typical technology company that will want to issue stock options to employees, raise capital through preferred stock, and expect a typical technology company life-cycle in which all surplus will be reinvested into the company (no distributions to owners) which is grown until the company is acquired or goes public, These factors would push you toward the C corporation form.

- Alternatively, will your company be operated for its cash flows over a long period of time, not necessarily managed for a public exit. In this case, a pass through entity such as an LLC or an S corporation may be preferable.

Those are the primary considerations. For those that want to dig deeper into the minutiae, what follows is a more detailed discussion of the differences between C corporations, S corporations, and LLCs (taxed as partnerships).

C Corporations. The biggest downside of corporations is that they are subject to double taxation. (The corporation itself is taxed on its profits, and shareholders are taxed when earnings are distributed to them.) However, the downside is diminished if the company intends to reinvest most of its surplus cash for growth. Moreover, the C corporation can accumulate net operating losses, which may offset profits in the future or have value to an acquiring corporation. C corporations can qualify for Section 1202 qualified small business stock, and for Section 368 tax-free reorganizations.

Limited Liability Companies. Technically, LLCs are disregarded entities in the eyes of the IRS. Under the Code, LLCs may elect to be taxed as a partnership, as a C corporation, or as an S corporation. When people refer to the tax treatment of LLCs, they usually mean an LLC that has elected to be taxed as a partnership. Taxed as a partnership, the LLC is a “pass-through entity” that is not taxed. The members are taxed according to the amount of profits that are allocated to them per the terms of the operating agreement. Allocations of profits and losses need not necessarily follow ownership percentages, they can be specially allocated per the terms of the operating agreement, although accounting and compliance gets more complicated when it does not. Investors can offset their other income from their share of LLC losses. Another advantage of partnership taxation is that appreciated assets can generally be distributed to partners/members tax free. (This can allow tax-free spin-offs of subsidiaries and other assets to the members.) Appreciated property (such as developed software, for instance) can be contributed to the LLC tax-free (without a “control requirement”). Lastly, redemptions of membership interests are a deductible expense to the LLC.

S-Corporations. Technically an S corporation is an election filed with the IRS, not a form of entity. LLCs, as well as corporations can be taxed as an “S corporation”. An LLC that makes an S election will be an S corporation in the eyes of the SEC, but it’s corporate governance matters will still be controlled by state law and the LLC operating agreement. Like an LLC taxed as a partnership, an S corporation is a flow though entity with a single layer of tax. S corporations convert easily to a C corporation. (Actually they convert automatically to a corporation if the company does anything to blow its S election, such as exceed 100 shareholders, accept a foreign shareholder, or issue preferred stock.) As with C corporations, Section 368 tax-free reorganizations are available.

An S corporation structure may result in the reduction in the overall employment tax burden. One difference between S corporation taxation and partnership taxation is that owners of LLCs can not be employees of the company. All member draws are subject to self-employment tax. With S corporations, owners may be reduce employment taxes by taking part of their income in salary (and paying employment taxes on that) and taking the rest of their income as a distribution. S corporation shareholders who are employees are taxed as employees and receive a Form W-2, not a Form K-1. As long as the salary is reasonable in the eyes of the IRS, the income taken as a distribution is not be subject to employment tax withholding.

Traditional stock options are available for S corporations, as long as the exercise price is a fair market value and doesn’t have any unusual terms that would cause it to be characterized as a another class of stock.

In summary , here are reasons you may choose one entity form over another:

C corporation because:

- Predominant model for tech start-ups (equity offerings and IPOs)

- VCs usually won’t invest in LLCs

- You will have foreign, corporate, or non-profit investors

- Retention of earnings/reinvestment of capital

- Qualified small business stock (Section 1202)

- Section 368 tax free reorganizations available

LLC (taxed as partnership) because:

- Single level of tax

- Flow through entity that allows: multiple classes of units, foreign members, over 100 members

- Investors can use operating losses

- Business will be operated for cash flows

- Tax-free distributions of appreciated assets

- Tax-free contribution of appreciated property without “control requirement”

- Special allocation of tax attributes (such as specific gain, loss, income or deductions)

- Redemption of partnership interests are deductible expenses of the LLC

S corporation because:

- Simple flow through entity with single level of tax

- Easy to convert to C Corporation

- Can minimize employment taxes

- Investors can use operating losses

- Business will be operated for cash flows

- Traditional stock options are available (as long as exercise price is at market value)

- Section 368 reorganizations available

But, S corporations are limited to 100, domestic, non-corporate shareholders, one class of stock. Shareholder redemptions are not deductible. Lack of ability to allocate profits, losses, attributes other than pro rata.

What are the different types of equity?

Equity refers to an ownership interest such as shares of stock in a corporation, a membership interest in a limited liability company, or a partnership interest in a partnership. Technically, an LLC member has only one membership interest. So it is incorrect to refer in the plural to a member’s “membership interests”. However, a member’s (single) membership interest can be represented by multiple “units”, just as a shareholder’s corporate ownership interest is represented by shares of stock. If membership interests are to be represented by units, it will be provided for in the company’s LLC agreement.

Rights to buy or convert into stock, a membership interest, or a partnership interest are considered contingent equity interests. The most common types of contingent equity are stock options, warrants, and convertible notes. Preferred stock is a form of equity that converts into another class of stock (common) according to certain contingencies.

A properly prepared capitalization table will show all contingent equity. See this post explaining what a “fully-diluted capitalization table” is.

What is pre-money value? How do you calculate it?

Pre-money value is a metric used by investors that tells them the price of their investment without having to know the number of shares outstanding. Pre-money value refers to the pre-investment value of the enterprise that is implied by the per-share price of the stock being offered and the number of shares outstanding. Because it is adjusted for outstanding shares, the metric allows investors to compare prices across different investment opportunities.

If the issuing company has a simple capitalization table, pre-money value is simply the per-share price to be paid by the investor times the number of shares and contingent shares outstanding before the investment. For example, if a company is offering preferred stock for $0.50 per share, and there are 10 million shares outstanding, the pre-money valuation is $5 million dollars. A company that is offering shares for $1.00 and has 5 million shares outstanding also has a pre-money valuation of $5 million.

As with capitalization tables, pre-money value can be calculated based on outstanding shares only, or on “fully-diluted” shares, meaning that contingent equity such as stock options, warrants, and convertible notes are included in the calculation. Investors will expect pre-money valuation to be based on a fully-diluted cap table, and that is how you should always calculate the metric unless there are special reasons for not doing it that way. A fully-diluted pre-money valuation will be higher (because the share price is multiplied by more shares). Intuitively this makes sense because if an investor can be diluted by contingent equity, they will essentially have to pay more (buy more shares) to achieve the same percentage ownership of the company.

Above, I said that for simple cases the pre-money valuation can be calculated by multiplying the share price times outstanding shares. The pre-money value metric has less explanatory value if the company is offering warrants in conjunction with the stock. To see why, look at the more complete formula for pre-money valuation:

Post Money Valuation = new investment * total post investment shares/shares issued to new investor

Pre Money Valuation = Post Money Valuation – new investment

Dividing new investment by the number of shares issued to the new investor equals the per-share offering price. So doing a little algebra, you can see that, with a simple capitalization table, the above formulas reduce to:

Post Money Valuation = offering price * total post investment shares

Pre Money Valuation = offering price * total post investment shares

But the formula is not so simply reduced if warrants are offered because the warrants have an exercise price. Should the exercise price be considered part of the new investment? It is not paid at the time the investment is made, but it will be if the warrants are ever exercised, and the exercise price will then benefit all other shareholders and be shared if the company is being sold or otherwise liquidated. I have seen it done three different ways:

- First method: The warrants are completely excluded from the calculation – it is not usually done this way, because the warrants will be included in the fully-diluted capitalization table.

- Second Method: the exercise price is ignored but the number of warrant shares is included with post-investment shares – this is the way I see it done most often, but significantly understates the pre-money valuation in my view.

- Third Method: the exercise price is included in the new investment and the warrant shares are included in post-money shares – this makes more theoretical sense to me, but an argument can be made that for large exits, the exercise price becomes less significant so that the Second Method is more comparable to pre-money values where there are no warrants.

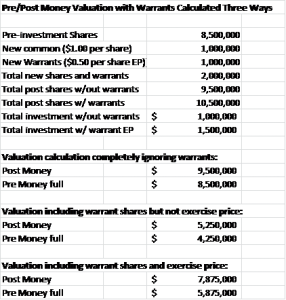

To get a sense of the difference obtained by using the three different calculation methods, look at this numerical example where 1,000,000 shares are being offered for $1.00 per share, and where each share comes with a warrant for one share with an exercise price of $0.50.

If you want to play with the numbers you can download the spreadsheet here.

Pre-money Value Calculated Three Ways with Warrants

As you can see there is a significant difference in the resulting value. Including the warrant shares in the calculation but not including the warrant exercise price yields a significantly lower pre-money valuation. Issuers will obviously like this metric, since a lower pre-money valuation implies investors are getting a better deal. Investors, if they haven’t looked too closely at how pre-money value was calculated, may assume that the exercise price was concluded.

So which valuation method is correct? None are necessarily correct or incorrect. They are just metrics that are useful for evaluation an investment. What is important is that everyone understands how the metric was calculated. To protect themselves from later claims of misrepresentation or securities fraud, issuers should be sure to clearly state which method they used in calculating pre-money valuation.

One take away from tall of this is don’t offer shares with attached warrants unless there is a good reason to. Usually there is not, and simple is always better.

What legal documents are necessary to start a company?

One can form a new corporation in minutes on the Secretary of State website, but much more documentation is required to establish rights and protocols with respect to ownership and management of the corporation.

To do it right, all of the documents listed below would be necessary in a corporation that is preparing to grow without legal hiccups. Fortunately, over the years, this documentation has become fairly standardized, and is not expensive to prepare.

Formation of Corporation: |

|

| Master Business License | Required by the State of Washington. |

| Local Business License | May be required by your local city or county. |

| Articles of incorporation | This is the foundational legal document of the corporation. It is required by statute. It establishes the classes and number of authorized shares, the rights and preferences of the stock, fiduciary and liability standards for board members, any special voting requirements, and other fundamental corporate matters. |

| Bylaws | The Bylaws establish rules regarding the board of directors, shareholder meetings, and other matters. Sometimes they contain indemnification rights for officers and directors. |

| Organizational resolutions | These first resolutions of the board of directors authorizes the first issuance of stock, appoints officers, establishes authority to open bank accounts, and other matters |

| Subscription Agreement | This is the agreement between the company and a purchaser of stock. Depending on choices they make, founders may have a simple subscription agreement, or they may have extensive documentation for restricted stock. |

| Stock Certificates | The document that certifies to a shareholder’s ownership of shares. |

| Stock Ledger | Ledger that shows the history of all issuances, transfers, and cancellations of stock. |

| Cap Table | The Capitalization Table is derived from the Stock Ledger. It shows the current ownership of the company, amounts paid and percentage interests. It includes options, warrants, convertible notes, and other rights to purchase or be issued stock of the company. |

| Shareholder Agreement | This sets forth agreements among the shareholders. Common terms are rights of first refusal and co-sale rights with respect to proposed transfers of shares, rights to approve certain major corporate actions, protocols if someone dies or gets divorced, and composition of the board members. |

| Asset Assignments | Usually the founders have created some IP before the company is incorporated. IP could include software, a patent application, a business plan, a potential customer list. All of these things should be assigned to the company when it is formed. There may be other assets, such as contracts or office equipment, that need to be assigned to the company. |

| S Election | For an S Corporation only, a document filed with the IRS that establishes the company’s election. |

| Limited Liability Agreement | For a limited liability company, the Limited Liability Company Agreement (sometimes called an Operating Agreement) will replace the Articles of Incorporation, Bylaws and Shareholder Agreement. |

Equity Compensation: |

|

| Founder Restricted Stock Agreement | Founders often impose buy-back restrictions on their stock that incentivize founders to stay with the company. See my post on the subject. |

| 83B Election | If the founders take restricted stock, the 83B election is a necessary form to file with the IRS to obtain the desired tax treatment. |

| Stock Option Plan | To issue stock options qualified for certain tax treatment, the options must be issued persuant to a written plan approved by the board of directors and the shareholders. |

| Employee Stock Option Agreement | This document contains the Grant Notice, which sets forth the number, type, exercise price, and other terms of the the options. The Stock Option Agreement, together with the Stock Option Plan and other incorporated documents, establishes and governs the employees rights with respect to the granted options. |

| Authorizing Resolutions | The board of directors and shareholders must approve the stock option plan, including the amount of shares set aside for the plan. |

Human Resource: |

|

| Employee Offer Letter | For the general employee, this agreement will document employment-at-will status and clarify compensation and benefits. |

| Form Independent Contractor Agreement | Most startup companies find it necessary or beneficial to hire consultants or other independent contractors. A well drafted Independent Contractor agreement will provide for important terms such as the nature of the relationship (not an employee), scope of work, payment terms, and most importantly, ownership of intellectual property created under the contract. |

| Worker Intellectual Assignment Agreement | The company should have a form confidentiality and intellectual property assignment agreement for employees and for independent contractors. |

Other Agreements |

In addition to the above, a company may have supply agreements, customer agreements, distributor agreements, service contracts, agreements with advisors, and promissory notes from founders or other supporters to the company. |

Tahmina Watson quoted in Seattle Times article on Startup Act 2.0

Startup Law Talk immigration specialist Tahmina Watson was quoted in this article in the Seattle Times about Startup Act 2.0. Seattle is full of immigrant entrepreneurs who start companies and create jobs for others. These entrepreneurs will benefit from passage of Startup Act 2.0, as well as the employees and business partners of the companies they create.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service eased visa restrictions on immigrant entrepreneurs last year but Watson is among those who would like to see further changes to the system. Immigrant entrepreneurs can now get H-1B visas, it is extremely difficult for these business owners to remain in the U.S. beyond the six years typically allowed. There is no easy path to a green card for self-employed entrepreneurs. Hopefully the Start-Up Act 2.0 will address that.

Should founders take restricted stock?

First off, we need to distinguish two definitions of restricted stock. The term restricted stock also refers to stock that is restricted from public transfers under the securities laws because it has not been registered with the SEC and state securities agencies. This post is about founder stock that is restricted in the sense that the company has the right to buy the stock back if the founder leaves the company. Founder restricted stock typically has the following characteristics:

- It is issued pursuant to a Restricted Stock Agreement between the founder and the company.

- At least part of the stock is subject to repurchase by the company at the original purchase price if the founder leaves.

- The restrictions on the stock, or in other words, the company right of repurchase, usually lapses according to a vesting schedule over two to four years, similar to stock options.

- For tax efficiency, stock is ideally issued at the earliest stage of the company, when the value of the stock is low.

- The founder makes an election under Internal Revenue Code Section 83(b) to include the value of the stock (in excess of the price paid for it) in the founder’s gross income for that year, which allows the founder to have capital gains treatment on the appreciated stock when it is later sold.

- Although the stock is not vested (it is still subject to the buy-back right) it has all the rights and privileges of issued stock, including voting and distributions.

Although it may be deemed burdensome, restricted stock serves at least three purposes that are mutually beneficial for founders:

- It motivates founders and other key employees to stay with the company and do their fair share.

- It establishes a pre-agreed protocol for easing out founders who have lost interest or underperform. (If a founder is perceived to be at higher risk than average to be tempted away to other projects, it is also possible to impose on the vested stock a buy back right at fair market value – as opposed to original purchase price for unvested stock.)

- Investors appreciate 1 and 2. In some cases, investors have required founders to accept buy-back restrictions on their stock

Restricted stock can be particularly useful in early stage companies where one or more founders are not working full time on the project. In such cases, rather than termination of employment, it is failure to contribute the minimum amount of service to the company that triggers the buy-back right. A clause like the following in the founders’ mutual restricted stock agreements seems to work well to keep founders doing their share of the work:

“Service” means at least an average of 20 hours of weekly service to the Company if Founder is not otherwise compensated (e.g., as a full or part-time employee). Founder will be assumed to be performing Service for the Company unless he receives a written notice from the other two Founding Shareholders that, in their view, Founder is not meeting the service requirement, in which case Founder will have 30 days to cure the failure.

If you decide to use restricted stock, it is wise to consult with an attorney or accountant, particularly with respect to the tax aspects and the 83(b) election. The 83(b) election must be filed with the IRS within 30 days of when the stock is originally issued.

How do I protect IP created by contractors and volunteers before I incorporate?

Before any start-up is formally incorporated, there is always a period when the founders have developed intellectual property in the form of market research, the business plan, perhaps trademarks, and often software code. Sometimes formation of the business entity is delayed too long, creating unintentional claims on the ownership of the business or its assets. But even when transition to the state-organized entity is timely, care should be taken beforehand not to create unintentional ownership claims on your intellectual property or your business itself.

First Caution: Don’t form an unintentional partnership. Unlike a corporation or a limited liability company, a partnership does not need to be formally organized with the state to exist as an entity. Under Washington law, a general partnership is formed anytime two or more people associate as co-owners to carry on a business for profit, whether or not they intend to form a partnership. A formal written agreement is not necessary. See RCW 25.05.055. As a founder, you will probably seek input and advice from many people as you are starting to form your business concept. Friends and family may help you work on your business plan, create a web site, or even assist with writing code. You may think they were donating their effort. But they might think they were your partners. Moreover, they will own the copyright to any work product , unless they assign it to you or the business. A frequent issue arises when two friends start work on a project, but one loses interest and stops contributing. The other keeps going but the relationship between them was never settled. Then when the business grows and becomes valuable, the non-contributing partner comes back and wants a share of the business. These kinds of situations are not unusual. Indeed, the majority of start-ups probably experience them to some degree.

So what are your available strategies at the pre-formation stage?

- Don’t take any help. (Not optimal and sometimes not even practical.

- Take help from only family members and close friends who you trust completely. (Without taking further precautions, this strategy risks damaging relationships. Any lawyer can give you examples of family members and friends whose relationships have been destroyed over business disputes. If you do need to do business with family and friends, I advise more documentation rather than less. Having an agreement in place beforehand can keep minor dissatisfactions from festering into real problems.)

- Use an independent contractor agreement with an IP assignment (see below), and pay the contributor a small amount for their work (even if payment is in something other than cash).

- In all cases, be very clear in your emails and other communications. If you decide not to pay them for their work, state clearly in a written document that the contributor is donating the work to your project without expecting anything in return.

- Actually make them a partner. If you do decide to make a contributor a partner, it may be a good time to consult an attorney or at least an experienced business person. You should have a written agreement in place. There are a host of issues that go into a forming a business with co-founders, not the least of which is how to divide up percentages in a fair way that leaves breathing room to issue stock in the future to financial investors, key employees, and other employees. Other issues to work through are control, tax strategies, salaries and distributions, terms of departure, and so forth. If you are ready to take on a partner, it’s probably worth the investment to consult a lawyer or accountant on entity choice.

Second Caution: Use Independent Contractor Agreements, even if you are not incorporated yet. If you pay someone to develop software, you own the code, right? Not necessarily so. Non-employees (i.e., independent contractors), retain the copyright of works they create unless the work product falls into certain designated categories that qualify it as “work made for hire”. 17 U.S.C. § 101 Most software development projects don’t fall into one of the enumerated categories for work made for hire, which is why you should have the developer (or logo designer, etc.) sign an independent contractor agreement. A well-drafted independent contractor agreement will have a work made for hire clause, and just to be safe, a backup clause that assigns the work product to the hiring entity. If you are a founder who has not organized a business yet, you are the hiring entity. The form of Independent Contractor Agreement that we have made available for downloading can be adapted to individuals who haven’t formed an entity yet.

Third Caution: When you do form an entity, assign the assets and contracts to the entity. One thing I see over and over again is that founders forget to assign their assets and contracts to the entity after it has been formed. It is a fairly simple process to go to the Secretary of State website, set up a corporation or a limited liability company, get your business license, and start doing business. But none of what you have created or produced before the company was formed is owned by the company unless it has been assigned to the company. When it comes time to raise capital, sophisticated investors will look back to all of your material IP to see when it was created and by whom. You will need to be able to show that it was created by employees of the company, or assigned by independent contractors to the company or to the founder, who in turn assigned it to the company. Usually the founder assigns all of the IP of the business to the company at the time it is formed and initial stock is issued. In addition to the business plan, market research, logos, trademarks, software and other IP, other assets such as account balances, computer equipment, contracts and leases need to be assigned to the company at the time it is formed.